Excerpted from Rao Yi Science WeChat Official Account

Table of Contents

Open Table of Contents

Establish good records when you’re young

Older people are hard to misunderstand because they have many records. If someone wants to spread rumors, they can’t succeed because you have records. If someone criticizes you for lacking in some aspect, you have records to refute or show you have strengths in other areas.

The younger you are, the fewer experiences you have, the more important it is to build records.

Graduate school is your first step into a semi-working state. There are exams, but they’re not that important. What’s more important is records.

Your records are your gradually accumulated career, life.

How to leave records?

One: Use a research notebook to record your scientific ideas, experimental designs, results, analyses, conclusions, including repeatedly recording your own mistakes, correction processes, etc.

Decades later, you can see from the notebook how you evolved from an enthusiastic but naive graduate student, from a young person who often encountered difficulties and needed to seek help, into an independent, mature scientist.

Two: Use your words and actions to leave records of you in others’ minds. Whether you have passion and insight for science, whether you’re warm and friendly to classmates, whether you can establish scientific communication with teachers… Your classmates, colleagues, teachers will all have records of you; even no impression is a kind of record.

Decades later, people will still evaluate and recall you based on the records in their minds of you

For records, what you young people should learn most from is the Chinese Workers’ and Peasants’ Red Army that set out from our Jiangxi.

From 1927 to 1934, not many people could foresee the Red Army’s later success. Outside Jiangxi, there were many warlords dividing territories, the Red Army’s material resources were far inferior to some big warlords. But the Red Army had lofty ideals, national organization, high confidence.

In 1934, the Red Army was forced to leave Jiangxi, undertaking what later became known as the Long March, unable to carry many things, only strategic necessities.

Among the items they considered indispensable, there was one very special: the telegrams they sent among themselves.

After reading the telegrams, after the information in the telegrams was implemented, why not discard the telegrams to lighten the load? Carry food, carry guns, carry bullets, or just reduce the pressure during the march?

They said, in the future we will check the telegrams, look at history.

The Red Army had few people over 30, mainly in their 20s and younger. On the Long March, lacking ideals and confidence would make people leave the team. But among this batch of young people, some had very high self-respect and confidence, believing they were creating Chinese history.

They preserved the telegrams because they were full of confidence in their future, even when the situation was dangerous.

Facts prove that these young Red Army members who believed their records were important and needed to be well preserved created China’s history and also influenced world history.

I hope young students, through their own scientific notes and behavior, establish their own records, establish others’ records of themselves.

Addendum: August 2, 2021

I have always advised students to keep records, not for others, but for themselves: the one most concerned with one’s own history can only be oneself.

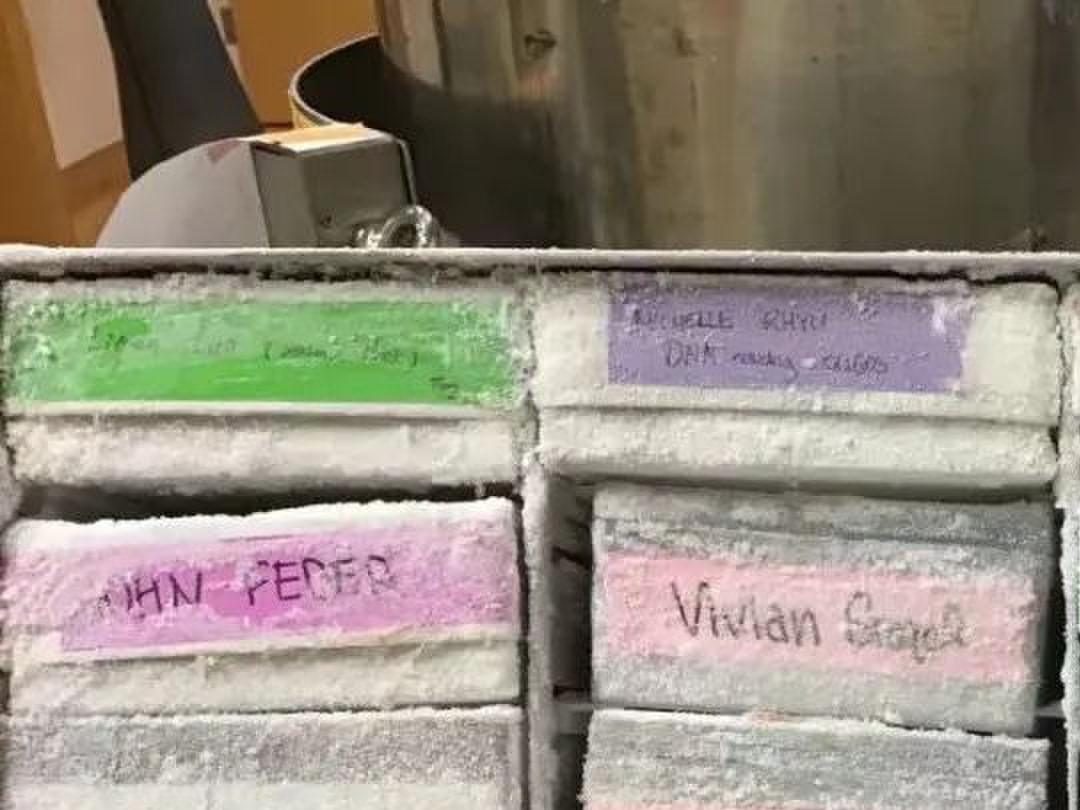

Recently, there was a photo from the Jan Lab at UC San Francisco where I did my graduate studies, the fridge had experimental supplies from people who had worked in the lab before, with a box labeled “me, 1991 (departure time).”

I estimate it’s DNA. At that time DNA was precious, cloning a gene was the main work of my six years of graduate studies in the US (previously I had two years in Shanghai, never felt the time was long in eight years).

This kind of gene cloning isn’t something you can do with PCR even now, but need to find the DNA where the mutation is based on fruit fly phenotype. After getting it, reintroduce normal DNA into mutant fruit flies to rescue the mutant fruit flies. The whole process is similar to finding a patient with mutant DNA, then reintroducing normal DNA into the patient for gene therapy, proving this DNA segment indeed carries the gene causally related to the disease (this was the category, couldn’t do it to humans at the time, but could to fruit flies).

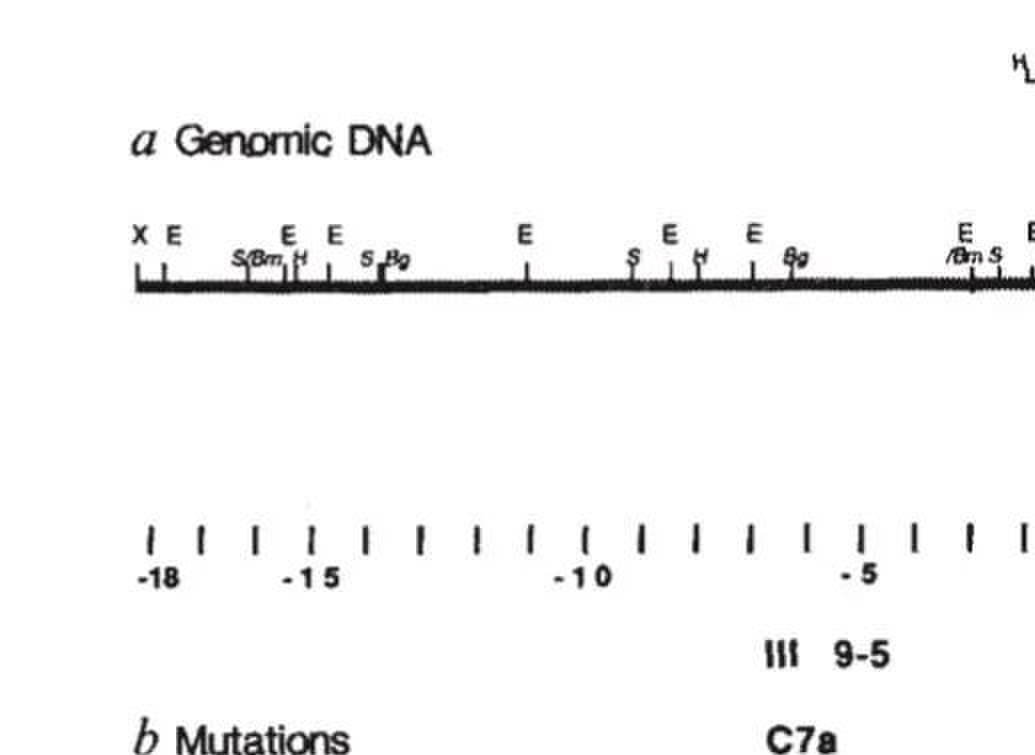

Shows a segment of DNA, two independent transposon insertions in mutations, three small segment deletions in mutations. PWB is the segment used for “gene therapy”, introduced into fruit flies via transposon, and proven to treat mutant phenotypes.

Thinking about it this way, Chinese students who did the full process from cloning genes to reintroducing genes for “gene therapy” in the 1980s, there might be no more than ten. At that time, in higher animals (mice, humans), generally only half was done (clone genes, or transgenes). Researchers doing gene therapy for humans generally hadn’t done gene cloning. Researchers doing gene cloning generally didn’t do gene therapy. Because cloning and “therapy” both steps were troublesome, generally only one step was done.

For studying lower animals, like flies and nematodes, we all did both steps.

But at that time, the few Chinese students doing fruit flies and nematodes could be counted, those who did the whole thing from start to finish should be among these people. Of course, today the gene therapy methods applicable to humans are different from fruit fly methods, but the concepts are the same, the principles of technology are the same, just different specific vectors and genes.

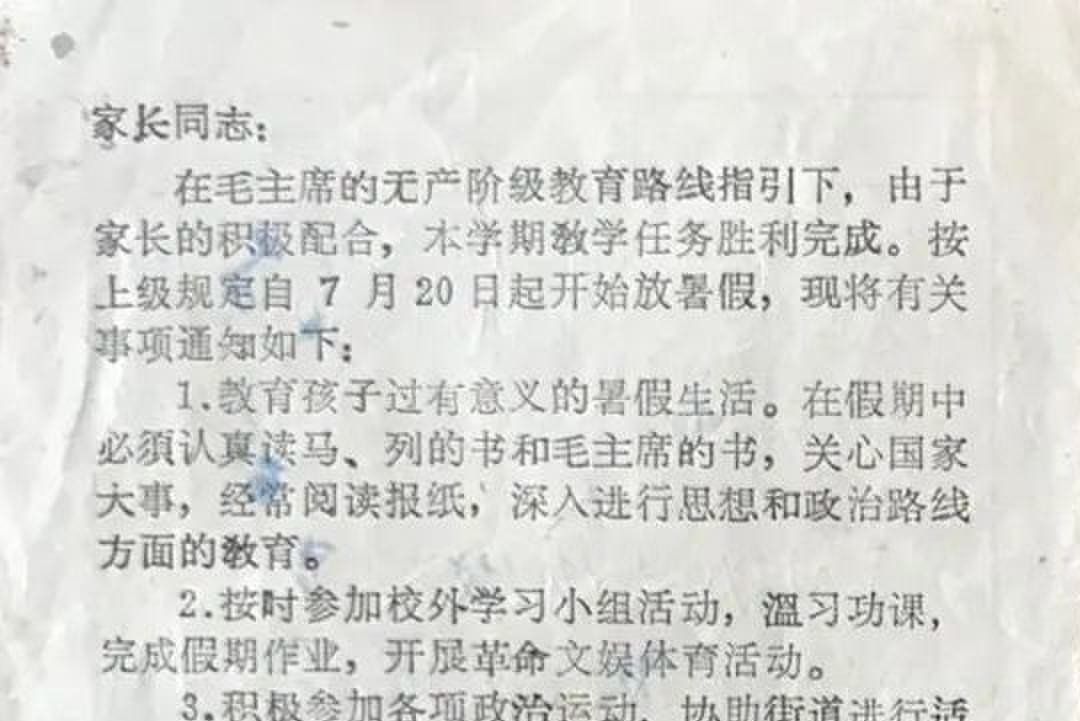

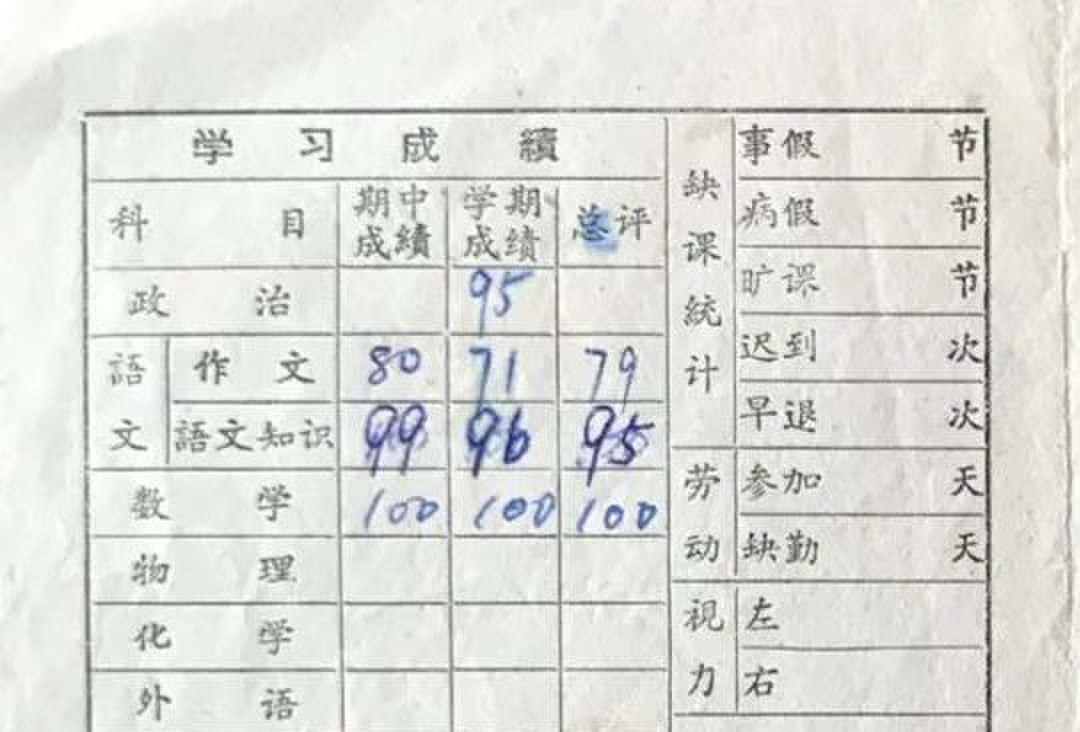

Records are hard to keep complete. I might have all my transcripts. Elementary school was the last semester of fourth grade transferred from my parents’ commune (Liu Gong Temple in Qingjiang County, now possibly Liu Gong Temple in Zhangshu City) to Nanchang. After that I have transcripts. Probably in the countryside there were no transcripts, only some kind of report. Leaving early transcripts was probably my mother. Later I might have kept them too, so I have transcripts up to my US graduate studies.

When moving before, I carried the main items.

Unfortunately, in the fourteen years back at Peking University, I moved five labs, and during that period, losses finally occurred.

In 2007 when I returned to China, Peking University gave me a very small lab (experimental space plus office 60 square meters), so I had to continue using the lab at Beijing Institute of Life Sciences. For Peking University’s life science recruitment, at that time I couldn’t expose the space limitation problem, could only solve it gradually.

For several years I commuted daily (generally morning office at Peking University, afternoon lab at Beijing Institute). After several years at Peking University I had over 100 square meters of lab, but two rooms in different parts of the corridor, one right next to the bathroom, not very good for work.

After resigning as dean, space improved, first a new comprehensive research building, then Wang Kefen Building. At Wang Kefen Building, lab space was finally sufficient.

I put a lot of effort into various methods to expand Peking University campus life science space. One method was to distribute in different aspects, not all in the School of Life Sciences, because if several spaces were all in the School of Life Sciences it would be hard to get repeated school support.

The biggest work on space was building the new Life Science Research Building (later called Lu Zhihe Building), got school approval in 2009, went through various…, on April 12, 2019, my own lab also moved into the new building, space problem completely solved.

Because it was after solving the life science college/discipline space, so it’s called “joy after life science joy”.

Can’t rule out that my office has the best view possibility in all of Peking University.

This is today’s record, good time for summer research.